Research

Secret to shape-shifting:

The genetic control of Daphnia predator-induced morphological defences is yet to be fully characterised. To realise the potential biomedical applications of understanding this environmentally-dependent example of morphological plasiticty, I have conducted preliminary investigations using RT-qPCR, immunoflourescence (Fig. 0) and microinjection in Japan.

# —– #

Predicting epidemic size and disease evolution:

Epidemics occur when a large number of hosts become infected relatively quickly. Since we are currently living in an era of broad environmental change, I developed a conceptual ‘Disease Cycle’ model during my PhD to link the size of past and future epidemics in a variable world (Fig. 1).

# —– #

Three major axes*:

1. DISEASE ARROW ONE – epidemic size determines the strength of parasite (or host) mediated selection.

2. DISEASE ARROW TWO – the mode of host-parasite co-evolution determines how the level of host and parasite population genetic diversity changes over time.

3. DISEASE ARROW THREE – the level of host (or parasite) population genetic diversity determines future epidemic size.

# —– #

*In addition, each link in the Disease Cycle is set within the context of environmental change (triangle).

# —– #

After reviewing the support for a conceptual Disease Cycle model from current literature and identifying areas for future research, it was shown how the model could help to promote a coevolutionary epidemiological approach to studying disease (sensu Galvani, 2003). In this sense bouts of recurrent disease are treated as part of an ongoing cycle of host-parasite coevolution.

# —– #

Geometric morphometric analysis:

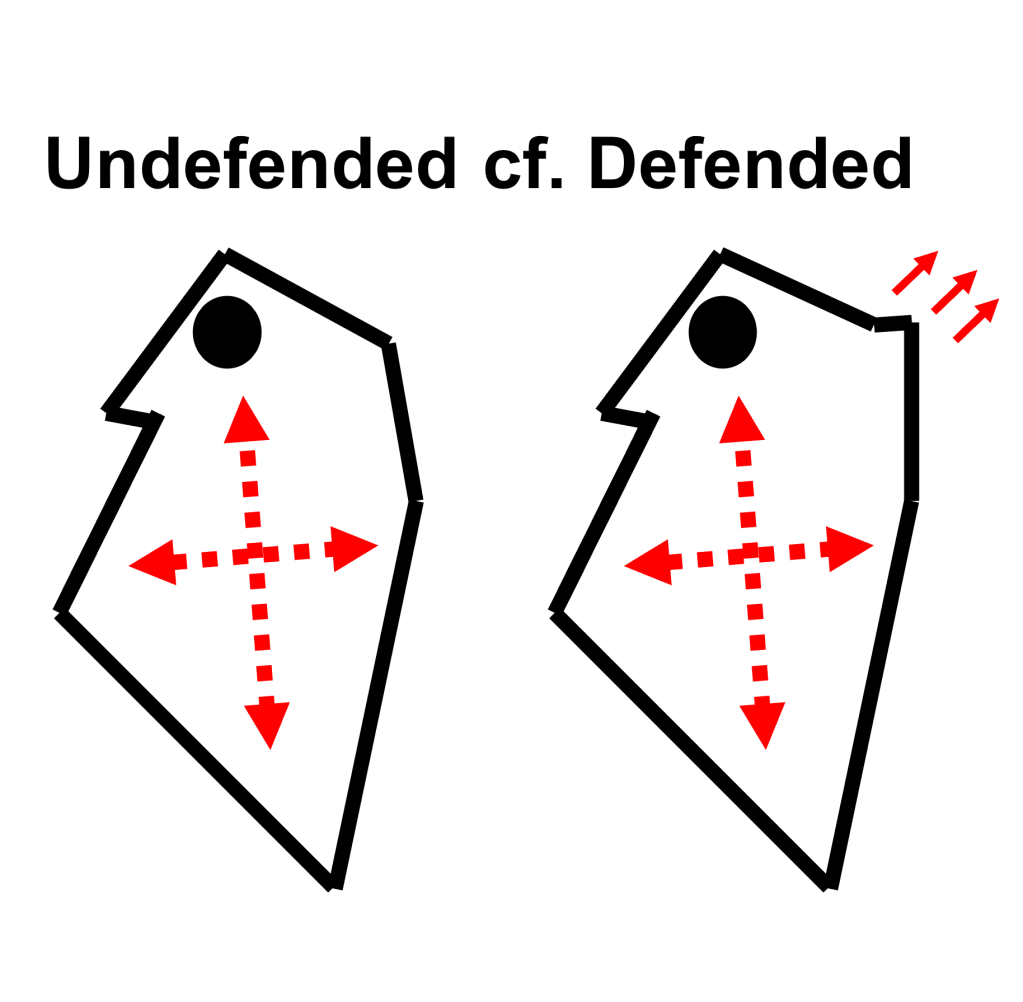

All living organisms adapt to environmental changes throughout their life cycle – a flexibility known as phenotypic plasticity. One key environmental factor is predation risk, or the likelihood of being attacked by a predator. In Daphnia pulex (a type of water flea), this risk can trigger defensive changes, including the formation of protective “neckteeth” against Chaoborus midge larvae (Fig. 2).

# —– #

While past studies have examined specific traits like pedestal size and spine count, this research explores how entire body shape responds to varying levels of predation. Findings reveal that, in addition to neckteeth, the head and body also change in size and shape, indicating a complex, integrated response involving multiple body modules. These results highlight how predation influences the overall morphology of D. pulex, offering a deeper understanding of shape variation driven by environmental pressures.

# —– #

Experimental host-parasite coevolution in the wild:

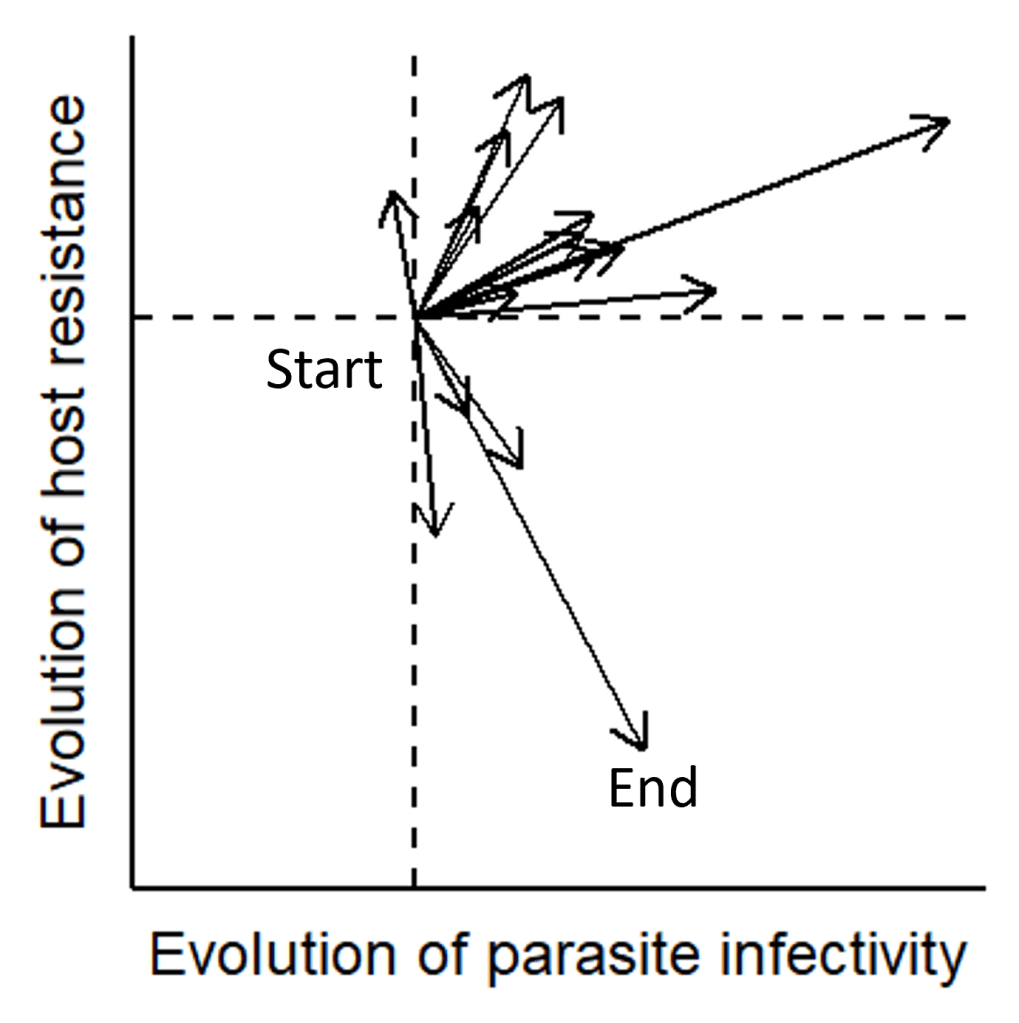

Considering the large amount of variation observed in both the strength and direction of coevolution in the wild (Fig. 3), a major question I seek to address in the field of evolutionary ecology is to what extent host-parasite coevolution is driven by a determinsitic processes and shaped by measures of environmental variation versus being completely random?

# —– #

By the end of the first year of my PhD, I managed to acheive a ‘world-first’ by using multivariate phenotypic trajecotry analysis to dissect three independent axes of host-parasite co-evolution (host evolution, parasite evolution and co-evolution itself) and showed that variation in the wider environment could explain the amount of divergence in co-evolutionary trajectories from populations with a shared origin.

# —– #